EMOTION

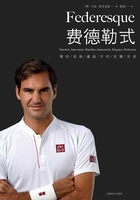

This beautiful tennis world was all out of focus for Roger Federer, pink-eyed and emotional while sitting on his chair at the 2018 Rotterdam tournament after becoming, at thirty-six, the oldest ever world number one. Just as tennis had been blurred for Federer less than three weeks earlier, when he had stood looking out at the Australian Open crowd through ‘my thick tears’.

In the emotionally raw moments that followed Federer winning the Melbourne title, he couldn’t even see that his friend Rod Laver, sitting in the arena that bears his name, was taking pictures with his phone. For everyone inside the stadium, as well as for the millions watching his champion’s speech from Switzerland and around the world, a truth about Federer was plain to see.

Twenty years after first sampling elite tennis–with an appearance at the alpine ATP tournament in Gstaad in 1998–Federer had scored a twentieth Grand Slam singles title, an unprecedented achievement for a man. That, in itself, was remarkable. What made it all the more astounding was Federer’s response-while there have been other occasions when he wept after winning a Grand Slam, starting with when he scored his first major at the 2003 Wimbledon Championships, this was the most emotional he had ever been. It was one of Federer’s boyhood idols, Boris Becker, who once remarked that competing on the international tour is so physically, mentally and psychologically exacting that tennis years are like dog years. And yet, even after twenty years in tennis, and even after winning more Grand Slams than any man in history, he was still as engaged as ever: ‘I like to care.’

At once, Federer is the most unemotional man in tennis, as well as the most emotional. As a child, Federer cried after losing matches at the Old Boys Tennis Club in Basel. As a teenager, he could be a hothead, prone to rages that would upset his watching parents. But, in his early years as a professional, he had morphed from a Swiss John McEnroe to Basel’s ownBjörn Borg; poised, impossibly calm in moments of adversity, and in almost total control of his emotions on a tennis court. Only the occasional cry of ‘chum jetze’, and there were a couple of those during his five-set victory over

Marin Cilic in the 2018 Australian Open final, ever gives a mid-match glimpse of the true desire and ambition and emotion that burn beneath that calm. But then, once a match is over, and Federer swaps a racket for a trophy and a microphone, he shows just how he adores playing, competing and winning. In those moments, Federer doesn’t want to cry, but he just can’t help himself. At the age of 36 years and 173 days, Federer was the second oldest man in the Open era, which began in 1968, to win a Grand Slam singles title, behind only Ken Rosewall, who was 37 when he took the 1972 Australian Open.

No doubt, pre-match tension had made Federer so tearful. All of Federer’s previous experience–this was his thirtieth Grand Slam final–hadn’t protected him from nerves, which had been ‘eating me up from the inside’ all Sunday as he waited for the evening final to begin. How would victory make him feel? On the flipside, what would defeat do to his outlook on the tennis world? Even after the final began, the nerves didn’t dissipate; if Federer’s record would suggest he’s extra-terrestrial, he’s also very human as well.

Holding the Norman Brookes Challenge Cup, which he affectionately calls‘Norman’, Federer had won ten per cent of all the Grand Slams during the Open era. What’s more, he had become only the fourth player to gather twenty majors or more, following a trio of women in Margaret Court, Steffi Graf and Serena Williams. He had also won a sixth Australian Open title, putting himself level with Novak Djokovic’s men’s record for the Open era. As Federer put it, ‘the fairytale continues’. Like the best fairytales, there had been a sense of jeopardy along the way. They were tears of joy. But they were also, and this told you how much he cared about tennis, tears of relief.